Interview with Peter Burr

from MM04, released November 2019

----

from MM04, released November 2019

----

Peter Burr is a Brooklyn, NY based artist who creates vast pixelated worlds populated by digital detritus. His aesthetics are at the intersection of geometric patterning and boundless computer generated zones. This interchange creates a fluctuation between flat abstracted CG spaces and expansive ever generating worlds. Questions of internet utopia, artificial intelligence, generative technology and the possible excess created therein arise in his labyrinthian multi and single channel works. Burr’s pieces have been commissioned by and featured at many prominent arts institutions and film festivals around the world including Sundance Film Festival, Ars Electronica, Institute for Contemporary Art at VCA, The Barbican Centre, and Times Square Midnight Moment among many others. In 2018, he was awarded a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship, and in 2019 he was a resident at Headlands Center for the Arts and is currently a Visiting Artist Fellow at SAIC.

----

Mostly Moving: Your visual style is very recognizable across all of your work, from installation to filmmaking, to projection. How did you develop that?

Mostly Moving: Your visual style is very recognizable across all of your work, from installation to filmmaking, to projection. How did you develop that?

Peter Burr: I used to be really interested in playing around with all the mass-media around us — all this trash. I liked reversing the steady flow of tv and films and games I grew up on to make new work. Over time I found that I was becoming more interested in exploring interior feelings, thoughts, questions that couldn’t be expressed through sampling my external environment. So I took some of the things I always explored on a formal level (ideas of density, illusion, oversaturation, overabundance) and kind of drained the vibrancy out of them just to see what was left. This exercise pointed me towards a simpler black and white palette. One thing I found interesting about working in pure black and pure white was that it conjured a density that my body was making — that my eyeballs were making just by watching. These errors of vision are hard-coded into all of us. And so for me, that visual style you ask about is the product of these restrictions — a new framework that started resonating with me a decade ago as my life got more complicated.

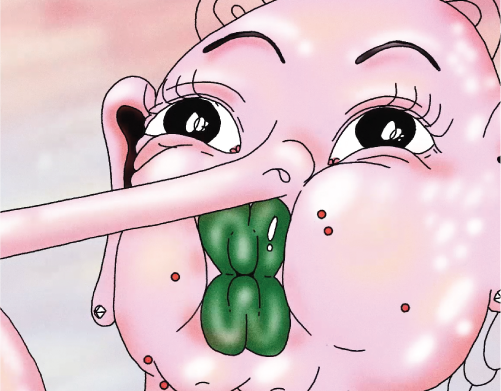

Remediator by Peter Burr

MM: Despite making films, your practice is much broader than that. Did you make a conscious effort to be more than a filmmaker or animator?

PB: When people talk about the art world, often that is shorthand for a world of high-end luxury objects. But there’s also an art world that’s simply a world of art and artists. That idea is really loose and really broad — its the art world I live in. This is a space that encompasses filmmaking, writing, drawing….. Sometimes it even encompasses doing nothing — just being alive in the world with a particular set of interests and an attitude. And so, I think because I didn’t study film in any formal way I came to making films as an extension of being alive in the world — meeting filmmakers and being interested in pushing a core set of values forward. And so at this point here I am, a filmmaker/animator/artist. I’m not sure what my label really is, but yeah…. I like to play around with these forms and experiment.

MM: How do you look at commission work versus your personal work?

PB: My commissions are typically not commercial, so it’s quite a tangled relationship. Normally when I’m getting a commission the budget is just enough to give that money to a collaborator or two. So I think of that commissioning money as a way to expand what I’m interested in and broaden my practice. It expands my personal work.

It's a strange business model. I’ve been working in this field for almost two decades and it’s never really been lucrative. For a long time, I was making a living running this project called Cartune Xprez where I was curating animation, taking the work on tour, and publishing DVDs. The money I made sustained the project and gave me enough to live on with super cheap rent and no health care and it was great because that was all that I needed. To a certain degree, it’s all I need now. My life now is not all that different and so I guess it kind of speaks to the trade-off of privileging freedom and flexibility versus a pursuit of financial wealth and economic success. In my life as an artist, I have just been presented with a certain reality that I’ve embraced.

MM: You build densely populated worlds that as a viewer we’re often only getting a glimpse into. Can you talk about how you think about the relationship between yourself, the viewer, and the work?

PB: When I think about the audience engaging with this work I think about it in really simple terms — just the act of being in the theater with a lot of other people experiencing this mass hallucination. I used to do long-form silent meditation retreats where on the final day the silence would be lifted after days and days of just being quietly inside myself. It’s really wild to sharply focus that feeling in the body when we talk to somebody for the first time. It’s such a rush of chemistry.

And so to speak about my past work, I can talk about a situation that is devoid of characters talking or conventional plot. A lot of really common chemistry is not present for the audience and so our attention sharpens around something else. I know experimental film isn’t for everybody, and so I think about that person who is able to think into this work — focus and defocus as the work dances and moves through time and space. There’s a very specific flow I attach this work to. Within that flow, there’s a world being built that has its own rules. These rules are different for every film. It’s one of the things that excites me about making new work.

MM: When collaborating, do you ever feel precious about your work or methods since your style is very recognizable?

PB: A couple years ago I came to CalArts to teach one session of a really technical software-oriented class and I used it as an opportunity to teach this unusual effect that I’m the only person I’ve ever seen use it. I trust that if anyone is interested enough in that technique to actually do something with it beyond class they’re gonna take that work and they’re gonna push it and do something new with it — something else with it — and then I’m gonna learn and be inspired from it. It’s that conversation, that back and forth, that I strive for.

I know that when an artist or designer is engaging with something superficially it’s not gonna have much weight so I try to be generous with sharing my work and methods. I’m just cautious when it comes to larger commercial applications. Over the years I’ve witnessed different communities of artists’ work get swallowed by the beast of mainstream culture. I’ve seen how that process can make their work not palatable anymore even to its original intended audience. I’m aware of that relationship between individuals and subcultures and the mainstream and I don’t think there’s a lot that can be done to mess with that. I suppose that’s why I think about connecting the heart of my work to the formal concerns in a really integrated way. This way of working has somehow formed a little forcefield around me while I keep moving my work forward…. pushing myself to respond to the world around me as it is happening and not stressing about style.

MM: In your work, there’s an intersection between abstraction and something realized. Can you talk about where these interests and style choices come from?

PB: I’m thinking in a really formal way about the technology that presents my work — like an LCD screen, for example. It’s so perfectly flat! It creates a really fun opportunity to go back and forth with that flatness and the pictorial depth of the world I’m inventing. I’m interested in creating moments where the space, the story, the people, and the environments that are being conjured can disappear and you as an audience member are just confronted with re-realizing yourself in this cinema or wherever you are. So I think about how this flat LCD space dissolves and extends into you and then back. It’s the somatic parts of cinema, this embodied way of viewing, that I really enjoy.

by Peter Burr

MM: You mentioned liking to give yourself challenges earlier with new projects. Is that where working with a game engine came from?

PB: I’ve been working with a game engine lately because it feels exciting. It has opened me up to using new systems in new ways that are really fun to explore. I like how these tools can integrate into other tools I’ve grown accustomed to using. The work becomes the product of a mix of different processes, but because I am engaging with new systems it opens me up to conceive new work differently than I’ve grown accustomed to.

MM: Does producing a body of work with multiple outputs (installation, cinema, multi-channel, etc.) give the work more of a life?

PB: With “Drop City”, a new work I’m developing right now, there is a lot to dig into. There’s a film version that you can grip on the internet; a 3-channel version that is museums/galleries/festivals show; and a desktop environment that’s sort of like a video game. Because all of these outputs are being conceived in tandem, the work generates the possibility of discovering new ways of being. In an ideal universe, this approach allows me to create something that is super unusual — something I’ve never seen before — which is often a primary motivation to keep working. I like trying to make something I haven’t seen before.

MM: What’s next for you? Do you see yourself moving past ideas of the labyrinth and dungeons, or will it always be part of your work?

PB: The answer to that question is contingent on so much. Part of what happens when you commit to doing something really ambitious is that you’re committing to the possibility of failing. It would be awesome to make a feature film that is super good and I love it and everybody loves it and then I want to make an even crazier feature film. But there’s also the possibility that I make it and it’s like “oh why did I even want to do that in the first place?” Same goes with making a video game right? It’s possible that it could go a bunch of different ways. That’s the big contingency. Also, as I continue to move through the world and meet people it really affects the kind of work I want to make. I can imagine if I met an awesome game designer that resonated with me thematically and we got along personally, maybe I would start making more video games. Or perhaps now that I have a big studio space for the first time since I moved to New York 10 years ago I will start spending a lot of time making drawings again. I’m not sure where that’s gonna go, but I can say right now I’m working on a looping video commission; I’m working on “Drop City” as an installation work and video game; I’m working on a new film; I’m making drawings with my new drafting machine; and I’m working on an architectural commission. Who knows where I’m gonna land with all this. But it feels like, as long as I push myself in a direction where I’m not sure where I’m gonna land, it’s all worth pursuing.

----

----

If you enjoyed this interview, please consider purchasing a physical copy.

Your support keeps the magazine running, thank you.

Your support keeps the magazine running, thank you.

© Mostly Moving 2020