Interview with Sean Buckelew

Ifrom MM01, released January 2019

Ifrom MM01, released January 2019

----

Sean Buckelew is a Los Angeles based animation filmmaker. His hand-drawn films capture a time in the not-so-distant past with a fixation on the early internet years that feels both nostalgic and poignant when juxtaposed against contemporary society. Through well-observed characters and strong writing & editing, he is able to draw profound meaning from otherwise everyday events. Sean’s films are cinematic and crafted with a realist style that is not always common with contemporary animation. This closeness to reality allows one to enter into the film and engage on a personal level. His films are well researched, excellently written, and display a technical and formal finesse that is not easily rivaled. Besides filmmaking, Sean is a champion of all things independent animation. He co-hosts a podcast with fellow indie animator Charles Huettner, is a member of the online animation collective Late Night Work Club, and is a programmer/curator for the GLAS Animation Festival.

----

Mostly Moving: I wanted to start by asking you to give a short background about yourself and how you started making films.

----

Mostly Moving: I wanted to start by asking you to give a short background about yourself and how you started making films.

Sean Buckelew: My name is Sean. I’m an animator born and raised in California. I started animating for the first time in high school when my Dad got me a copy of Macromedia Flash 3 from a computer show. There was a scene of people making little animated shorts on sites like B3TA and Newgrounds, and I emailed a couple of animators I admired (shout outs to Thomas Mannino and Joel Veitch) who pointed me in the right direction with learning the software and made me feel like I was part of an exciting creative community. I made a bunch of little comedy shorts that aren’t online anymore because they’re too embarrassing.

The ethos for making work in those early Internet days is still super inspiring to me. People just made things for the fun, no one was getting rich and “famous” for churning out content back then. And the software/hardware revolution made it possible for a lot of young people and non-professionals to become filmmakers and tell their stories (and have them seen by an audience).

I didn’t really start to identify as a filmmaker until I went to college at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. I took an animation class with Chris Sullivan, who ended up becoming a mentor and one of my all-time favorite filmmakers, and I started taking my animation work a lot more seriously.

MM: Regardless of the subject matter, your films all rely on strong drawing skills. Do you have any routines for keeping your skills refined?

SB: I used to do observational drawing in my sketchbook a lot, especially when I was doing my undergraduate studies in Chicago. I also took a lot of figure drawing classes because it seemed like the right thing to do to get better at animating. I think the generation of animators that grew up with The Animator’s Survival Kit as their sole snorkel for learning how to properly animate just took as gospel that figure drawing = better animation. I don’t do as much non-animation, observational type drawing anymore, but I still draw a lot when developing films and enjoy drawing as a meditative act.

MM: Each of your films feels like a complete package, with no detail missed. Can you describe how you start a project with the scope of the ones you’ve worked on?

SB: I think that’s maybe a byproduct of doing a lot of research around the context for any film idea. Ideas for me usually start as something really simple, like a single image or interaction, and then usually the “story” sort of folds out from doing research and developing a context for the original idea. It also helps that a lot my ideas are rooted in the real world, so it’s easier to pull details straight from experience or observation.

MM: It’s clear that technology, with an emphasis on early internet years, is important to your artistic vision. What is it that draws you to this subject matter?

SB: It’s probably a combination of finding that time period interesting and relevant to the present in a political context, and having personal experience that felt particularly visceral (which is maybe true for a lot of teenage experience, I just happened to spend a lot of those fragile teenage years in front of a computer). I think the latter helps me unpack aspects of early internet technology in an emotional way, and the former helps ground the personal stuff in a context that hopefully feels bigger than just nostalgia for dated computer things.

My Dad also worked at IBM and then started a non-profit in Oakland that refurbished and distributed computers to low income families (big up Tech Exchange!). He was a huge inspiration for a lot of things, but I think growing up thinking about the politics and inequities of technology had a big impact on me.

MM: While your films are all serious in nature, your Vimeo feed shows you aren’t afraid to have a laugh either. Where did projects like the 2017 & 2018 Animation Reel’s come from?

SB: I actually think independent animators have a hard time letting the funny stuff trickle into their work (myself included). I really love watching comedy, probably more than anything else, but when I sit down to make a new short, it almost always skews serious. I think this might be related to the state of independent animation in a broader cultural sense, that you’re default reactionary instinct is to go dark and serious since so much of popular animation is comedy for children.

Projects like my two “booby trapped” reels (an expression a guy at a studio used to describe them when they were trying to book me for a freelance job) were the result of the stupidest impulses. I think with projects like that, the ideas are usually so bad and immature, if you don’t act on the instinct to make it within five minutes of coming up with it, you’ll never actually make it. I think there’s real power in that kind of process, and it’s led to a bunch of videos that I’m secretly really proud of, but don’t really fit into my normal animation body of work. I did a collaboration with some friends called CG RIBS that was designed around that kind of spontaneous follow through on silly or stupid ideas, and our group motto was “never sleep on it”.

MM: With four staff picks and hundreds of thousands of views combined, It appears you’ve cracked the code for the short film online release (besides having a great film to start with). Do you feel like the online exposure translates to real-world success?

SB: I think this is a big question a lot of short filmmakers are dealing with. I’ve had a bit of a mental pendulum swing the last two years that is driving me back towards a more traditional rollout for a short that is focused primarily on festivals and less on the internet. It’s tied to the shifting of video platforms online and a desire to have my shorts screened in a more traditional cinematic context, which I think is still the optimal venue for watching anything. But I also love the internet and love the community of independent animators that I’ve met on Twitter and Vimeo.

I don’t think it’s ever a good idea to be so covetous over a short that you never put it online, especially if your goal with making shorts is to have the highest number of people see it. Having shorts online has allowed me to set up a practice where I can work professionally as a freelance animator, and continue to make personal work. But I’m also seeing now how the “prestige” of a more festival-focused rollout can give a film a different kind of life, both in the way people watch it and engage with it, and the long tail of how it comes online and fits into the development of future projects.

MM: Your films feature both well-written dialogue and storylines. How do you approach writing for your films?

SB: I was a hardcore non-script writer for a long time, and sometimes would avoid storyboarding to try to have the story process tied directly to the actual animating. I think that allows for more fun and spontaneity, but can also lead to big problems at the zero hour when you put everything together and find out it doesn’t really work. I also like recording with friends in casual situations that allow you to frankenstein a performance together afterwards that feels more natural/improvised.

A few years ago I started writing a lot more, inspired directly by my friend Joe Bennett, who got me into it and introduced me to the free scriptwriting Google app YouMeScript. So I spend a lot more time writing now, and coupled with a more traditional storyboarding process, I think it’s leading to slightly more structured stories and gives me a better sense of the bigger picture of a film earlier on in the process. It also helps a lot if you’re reaching out to actors/collaborators that aren’t your friends.

MM: Can you summarize your experience working with LNWC?

SB: Late Night Work Club was designed as an excuse for animators doing boring/unfulfilling freelance jobs to have a context and support group to make new, independent/personal shorts. It was also being organized by animators that hadn’t had much opportunity to travel see their work get exhibited at big festivals (plane tickets to Annecy are expensive). They wanted to remove the geographical element and exclusivity of the festival experience by making the anthology feel like a block of shorts you’d see at a festival, but dropping them online so everyone could see them at the same time.

For me, getting the first invitation email from Scott Benson that outlined the whole project idea and all the other artists who would be contributing was really exciting. I felt like I was on a bit of an island with my work prior to that: too character-driven for the hardcore experimental people, but too weird for the more traditional, narrative-focused side. I was also developing an interest in independent production models and thinking more seriously about how you could use the internet to distribute shorts. It definitely all converged with the Late Night Work Club crew, and I felt like that group really pushed me into becoming a more confident artist and the whole experience was very validating. I had finally found my community!

The actual experience of producing the two shorts for the anthologies wasn’t too different than any other film production, I guess. It was harder on the second one because I really was making the film late at night and on weekends and between jobs. Some people in the group made their films more publicly and others kept it private until the very end, wanting to surprise the group with what they had made. I think it’s an inspiringly simple framework for making work, and the barrier for entry for anyone else to do their own Late Night Work Club-esque project is pretty low. You just have to gather up some friends, commit to finishing something, and use each other as motivation (or guilt/fear of letting the group down, which can be also be a great motivator).

MM: You have an eye for cinematic flair that makes your films feel sometimes closer to live-action than animation. To what degree does live-action filmmaking influence your work?

SB: I think you subconsciously absorb so much influence from what you decide to watch or read or engage with, so for me, I like to watch live-action movies a lot, and it ends up being in the work because I’m just immersed in that language maybe more than I am in distinctly animated/drawn languages. I think also having films that are sort of based in the real world makes it feel more appropriate that the cinematic language be more “reality”-based. I also like making things feel smooth — when cuts feel continuous and move you along, I think it can help seduce someone into watching something that is conceptually or thematically strange or complicated. Live-action cinematic language is so hardwired into our brains, it makes it easier to accept and ground a person in strange realities when it’s used in an animated film.

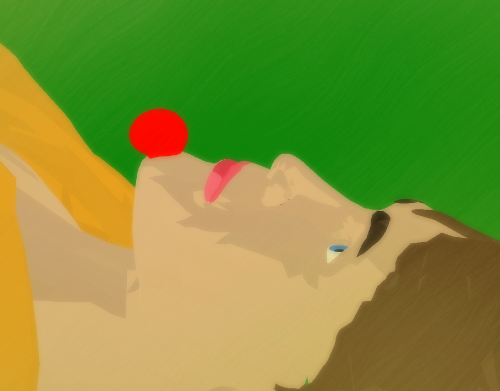

Production Still from Buckelew’s “Drone”

MM: You’ve begun production on a new short called “Drone”. Can you share any info about the film?

SB: It’s still in the early stages of production, but I’m very excited to be working on this film. It’s a satire about Predator drones, public relations, AI and sensationalism on the Internet. I’m doing a lot of things more properly this time around, got a bit of financing, and have been fortunate to bring on some extremely talented artists who are already doing amazing work on the film. Sorry I’m being a little vague but I think it’s still a bit early to say too much! I’m planning to do some Twitch live streams demonstrating some of the production pipeline, so make sure to smash that subscribe button.

----

----

If you enjoyed this interview, please consider purchasing a physical copy.

Your support keeps the magazine running, thank you.

Your support keeps the magazine running, thank you.

© Mostly Moving 2020